Building a Website with OCaml and Dream – Part 5

Type-safe HTML and OCaml Server-Side Components with a touch of Assets Management

Series

- Building a Website with OCaml and Dream – Part 1

- Building a Website with OCaml and Dream – Part 2

- Building a Website with OCaml and Dream – Part 3

- Building a Website with OCaml and Dream – Part 4

- Building a Website with OCaml and Dream – Part 5

Introduction

First, I want to give a huge shoutout to Chukwuma for dedicating his time to testing the code from my previous articles on Windows. Based on his feedback, I’ve updated those blog posts to include the necessary information to make the code work on Windows. It may not be perfect yet, but I’ll continue refining it as I receive more feedback.

Since this series is about documenting my journey of building a website with OCaml and Dream, I sometimes change my mind about things I’ve previously discussed. eml templates are one such case. Generally, I’m not a fan of DSLs for writing HTML in any language or framework — I prefer to stay as close as possible to raw HTML. Initially, I followed this approach while building a Games Index, adapting the concept of partials from Rails.

There’s nothing wrong with this approach, and if you prefer it, you can absolutely keep using it. It doesn’t significantly impact how we use Dream to create a website, nor does it introduce major changes in the tooling needed elsewhere in the code. However, I started feeling that type-safe HTML was a better fit for a functional programming language like OCaml. Plus, I was getting frustrated with having to choose between syntax highlighting for OCaml or HTML, but not both. After making the switch, I’m quite happy with the results.

That brings us to the topic of this article:

- Adding the Index view to the Games module as part of the traditional CRUD approach

- My implementation of views using Partials, then evolving into a Component-based structure

- Type-safe HTML with dream-html

- Asset management (with Stimulus JS as a bonus)

As always, if you have any remarks, questions, or suggestions, feel free to reach out. I might be a bad software engineer, but at least I have no ego about it!

CRUD: Index

Router, Handler, Domain

First, we need a route to display the list of completed games.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let routes =

[ Dream.get "/static/**" (Dream.static "static")

; Dream.get "/" Pages.homepage

; Dream.get "/games" Games.index

; Dream.get "/games/:id" Games.show

]

;;

This leads us to the implementation of the Games.index handler:

1

2

3

4

5

6

(* Previous code for the `show` function *)

let index request =

let* games = Game.all ~request () in

games |> Views.Games.Index.render |> Dream.html

;;

Now, we return to our Domain module to implement the all function.

Since we are displaying a list of completed games, the order of the list is important. We’ll sort it in descending order by completion date while keeping the option to modify the ordering if needed. Along the way, I discovered an OCaml quirk: functions cannot have optional arguments unless they also have at least one positional argument. To work around this, I added a unit (()) argument, even though the named argument ~request is mandatory.

For the all function, we build upon what we implemented in the previous article regarding SQL queries:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

let all ~request ?(order_by = "completion_date") ?(direction = `Desc) () =

let order =

match direction with

| `Asc -> order_by ^ " ASC"

| `Desc -> order_by ^ " DESC"

in

let open DB in

let open Lwt.Syntax in

let query = (string ->* t) "SELECT * FROM games ORDER BY ?" in

let all' =

fun (module Db : Connection) ->

let* games = Db.collect_list query order in

Caqti_lwt.or_fail games

in

let* result = all' |> Dream.sql request in

Lwt.return result

;;

Views

The view is straightforward, building on what we’ve already established. Each game entry in the list will display its cover, title, and rating (if available) while linking to the show page we built earlier.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

let index_data (games : Game.t list) : Templates.Games.Index.data =

List.map

(fun (game : Game.t) : Templates.Games.Partials.IndexGame.data ->

{ uri = "/games/" ^ game.id

; title = game.title

; rating =

(match game.rating with

| None -> "N/A"

| Some r -> string_of_int r)

; cover_url = game.cover_url

})

games

;;

let index games =

Templates.Layouts.Main.layout @@ Templates.Games.Index.render @@ index_data games

;;

For the eml template to be compiled by Dune, we need to add it to the dune file:

1

2

3

4

5

(rule

(targets show.ml index.ml)

(deps show.eml.html index.eml.html)

(action

(run dream_eml %{deps} --workspace %{workspace_root})))

The template itself uses Partial views to promote reusability and reduce code duplication. It contains a little more OCaml code than before, but it remains readable and maintainable:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

type game_data = Partials.IndexGame.data

type data = game_data list

let render data =

let li_content = String.concat "\n" @@ List.map Partials.IndexGame.render data in

<h1 class="text-red-800 text-4xl">Mes jeux terminés</h1>

<ul>

<%s! li_content %>

</ul>

Since partials are also eml templates, they need to be compiled as well. The dune file follows the same structure as before:

1

2

3

4

5

(rule

(targets indexGame.ml)

(deps indexGame.eml.html)

(action

(run dream_eml %{deps} --workspace %{workspace_root})))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

type data =

{ uri: string

; title : string

; rating : string

; cover_url : string

}

let render data =

<li>

<a href="<%s data.uri %>" class="flex items-center">

<img src="<%s data.cover_url %>" alt="<%s data.title %>" class="w-1/4">

<div>

<%s data.title %>

</div>

<div>

<%s data.rating %>

</div>

</a>

</li>

See? No need to stress about my change of mind regarding eml templates! They’re still easy to use and remain powerful, so you can continue using them while following this series.

From Partials to Components in EML Templates

The difference between partials and components is rather subtle. One way to put it (though you may disagree) is that a partial is a snippet of HTML meant for reuse in different places, whereas a component is a piece of code that produces HTML and can contain reusable logic. In my implementation, this distinction is even finer since eml templates are essentially glorified OCaml files. But bear with me!

Here again, keeping to partials is perfectly fine and has served the Rails community well for years. I just wanted to try something new and see how it goes.

Component Functor

Our components should meet the following requirements:

- They should be renderable (obviously).

- They should support rendering with encompassing tags — for example, wrapping the output in

<li>...</li>as in our earlier partial. - They should be capable of rendering a list of similar components. In the partial example, we needed extra code to render a list of partials.

- They should produce strings for the view so that type handling is not an issue.

This naturally calls for a functor, doesn’t it?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

open Containers

module Games = Games

module type COMPONENT = sig

type data

val render : data -> string

end

module MakeComponent (C : COMPONENT) = struct

type data = C.data

let render data = C.render data

let render_with_tag ~tag data =

let inner_html = C.render data in

Printf.sprintf "<%s>%s</%s>" tag inner_html tag

;;

let render_list ~tag data_list =

data_list

|> List.map (fun data ->

match tag with

| Some tag -> render_with_tag ~tag data

| None -> render data)

|> String.concat "\n"

;;

end

As I want Components to be real Ocaml files, we will use a PPX to generate the eml part of components.

1

2

; Add to dependencies:

(depends ... ppx_dream_eml)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

(library

(name components)

(libraries containers dream)

(preprocess

(pps ppx_dream_eml)))

(include_subdirs qualified)

And voilà, our first component!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

type data =

{ uri : string

; title : string

; rating : string

; cover_url : string

}

let render data =

{%eml|

<a href="<%s data.uri %>" class="flex items-center">

<img src="<%s data.cover_url %>" alt="<%s data.title %>" class="w-1/4">

<div>

<%s data.title %>

</div>

<div>

<%s data.rating %>

</div>

</a>

|}

;;

The view now uses the MakeComponent functor to render the component as a list:

1

2

3

(library

(name views)

(libraries containers components templates domain))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

(*===========================================================================*

* Game Index

*===========================================================================*)

module IndexGameCardComponent = Components.MakeComponent (Components.Games.Card)

let index_data (games : Game.t list) : Templates.Games.Index.data =

let games_data =

List.map

(fun (game : Game.t) : IndexGameCardComponent.data ->

{ uri = "/games/" ^ game.id

; title = game.title

; rating =

(match game.rating with

| None -> "N/A"

| Some r -> string_of_int r)

; cover_url = game.cover_url

})

games

in

{ card_components = IndexGameCardComponent.render_list ~tag:(Some "li") games_data }

let index games =

Templates.Layouts.Main.layout

@@ Templates.Games.Index.render

@@ index_data games

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

type data = { card_components : string }

let render data =

<h1 class="text-red-800 text-4xl">Mes jeux terminés</h1>

<ul>

<%s! data.card_components %>

</ul>

Dream-html and Type-safe HTML

I should probably call it PureHTML instead, as I won’t be using the parts of this library that interact with Dream — only its DSL for writing HTML in a type-safe way. Maybe one day, I’ll be convinced by other aspects of this library!

As the project grows, I’ve been thinking about its structure:

- There are quite a few folders now.

- I like to keep things organized, and since we’re working exclusively with OCaml now, do we really need a strict separation between

viewsandtemplates? - If everything is under

views, I don’t want to mix conceptual structures likecomponentsorlayoutswith domain-related folders likegamesorusers. - Alphabetical ordering isn’t always the best for semantic organization. In Rails, an underscore at the beginning of a folder name is ignored by the framework while removing it from the alphabetical sorting. I’ll mimic this behavior to improve file organization fro, the

dunefiles.

(I don’t have a clean solution for dune files themselves yet, so if anyone has ideas, I’d love to hear them!)

New Project Structure

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

lib/

└── server/

├── domain/

│ ├── date.ml

│ ├── date.mli

│ ├── dune

│ ├── game.ml

│ └── platform.ml

├── handlers/

│ ├── dune

│ ├── games.ml

│ └── pages.ml

├── views/

│ ├── _components/

│ │ ├── games/

│ │ │ └── card.ml

│ │ └── components.ml

│ ├── _layouts/

│ │ ├── dune

│ │ ├── layouts.ml

│ │ └── main.ml

│ ├── games/

│ │ ├── index.ml

│ │ └── show.ml

│ ├── pages/

│ │ └── homepage.ml

│ └── dune

├── dune

└── router.ml

If a page becomes too complex to fit neatly into a single view file, we still can use a layout to encapsulate the complexity.

Components Using PureHTML

Components remain conceptually the same, but instead of returning a string, they now return a PureHTML node, making them more type-safe.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

open Containers

open Fun

open Pure_html

module Games = Games

module type COMPONENT = sig

type data

val node : data -> node

end

module MakeComponent (C : COMPONENT) = struct

type data = C.data

let node data = C.node data

let html = to_string % node

let node_with_tag ~(tag : node list -> node) data =

let inner_node = C.node data in

tag [ inner_node ]

;;

let html_with_tag ~tag = to_string % node_with_tag ~tag

let node_list ?tag data_list =

data_list

|> List.map (fun data ->

match tag with

| Some tag -> node_with_tag ~tag data

| None -> C.node data)

;;

let html_list ?tag data_list =

String.concat "\n" @@ List.map to_string @@ node_list ?tag data_list

;;

end

Type-safe Views with PureHTML

Each view now has its own file, and eml templates are replaced with PureHTML nodes.

For example, here’s the updated Games.Index view:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

open Containers

open Domain

open Pure_html

open Pure_html.HTML

module GameCardComponent = Components.MakeComponent (Components.Games.Card)

let extract_data_from (games : Game.t list) =

let component_of_game : Game.t -> GameCardComponent.data =

fun game ->

{ uri = "/games/" ^ game.id

; title = game.title

; rating = Option.map_or ~default:"N/A" string_of_int game.rating

; cover_url = game.cover_url

}

in

List.map component_of_game games

;;

let render games =

let index_card_list =

extract_data_from games |> GameCardComponent.node_list ~tag:(li [])

in

Layouts.Main.layout

[ h1 [ class_ "text-red-800 text-4xl" ] [ txt "Mes jeux terminés" ]

; ul [] index_card_list

]

|> to_string

;;

This approach moves further from raw HTML but brings in more elegant, type-safe OCaml!

Managing Assets

Browsers cache assets aggressively, which can cause issues when updates don’t immediately take effect. A common solution is to fingerprint assets, ensuring each version has a unique name. There are several approaches to this, but the simplest and most secure method is to name assets after their MD5 hash.

However, this introduces a challenge: developers shouldn’t have to manually update asset references every time a file changes. The asset pipeline should handle this automatically by providing helpers to generate the correct paths while managing fingerprinting under the hood.

Additionally, I want to use Stimulus for my JavaScript needs. As a strong proponent of the no-build paradigm, I also want to manage my JS dependencies using Import Maps rather than a bundler.

The Plan

To achieve this, my approach is:

- Fingerprint every file in the

staticfolder when the server starts. - Map original filenames to fingerprinted versions, with a utility function to retrieve the correct path.

- Generate Import Map tags from both local JS assets and external libraries.

Since my setup must support both EML templates and my work with PureHTML, I’ll make sure the tag generation works seamlessly with both.

Fingerprinting Assets

The fingerprinting process follows these steps:

- Take the name of the asset

- Remove the extension

- Compute the md5 hash of the file

- Append the hash to the name

- Append the extension

Here’s how it looks in OCaml:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

module Fingerprint = struct

(* is_fingerprinted is a function based on a simple Regex *)

(* remove_from is the opposite of add_to, and a fuction based on the same Regex *)

let md5_of_file filename =

IO.with_in filename (fun ic ->

let digest = Digest.channel ic (-1) |> Digest.to_hex in

digest)

;;

let add_to filename =

match is_fingerprinted filename with

| true -> filename

| false ->

let extension = Filename.extension filename in

let basename = Filename.remove_extension filename in

let fingerprint = md5_of_file filename in

basename ^ "-" ^ fingerprint ^ extension

;;

let rename_file filename =

match is_fingerprinted filename with

| true -> ()

| false -> Sys.rename filename (add_to filename)

;;

end

Applying this to all files in static is straightforward:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

let recursive_file_list dir =

let rec aux acc = function

| [] -> acc

| file :: files ->

(match Sys.is_directory file with

| true ->

let new_files =

Sys.readdir file |> Array.to_list |> List.map (Filename.concat file)

in

aux acc (files @ new_files)

| false -> aux (file :: acc) files)

in

aux [] [ dir ]

;;

let fingerprint ?(path = "static/") () =

recursive_file_list path

|> List.fold_left

(fun asset_map filename ->

let original_filename = Fingerprint.remove_from filename in

let fingerprinted_filename = Fingerprint.add_to filename in

Fingerprint.rename_file filename;

StringMap.add original_filename fingerprinted_filename asset_map)

StringMap.empty

;;

Generating Import Maps

To ensure JavaScript dependencies are correctly loaded, the Import Map must:

- Reference fingerprinted assets.

- Include manually imported JS libraries from external sources.

- Generate both the Import Map JSON and preload tags for better performance.

Some browsers won’t load assets listed in the Import Map unless explicitly imported in the HTML, so we’ll generate both:

- The Import Map JSON (for

script type="importmap"). - The preload modules (for

<link rel="modulepreload">).

Here’s how that works in OCaml:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

module ImportMap = struct

type t = (string * string) list

let to_json (list : t) =

`Assoc [ "imports", `Assoc (list |> List.map (fun (k, v) -> k, `String v)) ]

|> Yojson.Safe.pretty_to_string ~std:true

;;

let to_module (list : t) = List.map (fun (_, v) -> v) list

let asset_rewrite path original_filename fingerprinted_filename =

let basename = Filename.basename original_filename |> Filename.remove_extension in

let directory = String.chop_prefix ~pre:path @@ Filename.dirname original_filename in

let name_without_underscore =

Option.get_or ~default:basename @@ String.chop_prefix ~pre:"_" basename

in

let module_name =

match directory, String.equal basename "_index" with

| Some dir, true -> Filename.basename dir

| None, true -> "index"

| Some dir, false -> dir ^ "/" ^ name_without_underscore

| None, false -> name_without_underscore

in

module_name, "/" ^ fingerprinted_filename

;;

let from_asset_map path asset_map =

StringMap.fold

(fun k v acc ->

match Filename.extension k with

| ".js" -> asset_rewrite path k v :: acc

| _ -> acc)

asset_map

[]

;;

end

let generate_importmap ?(path = "static/") (import_list : ImportMap.t) =

let importmap =

fingerprint ~path () |> ImportMap.from_asset_map path |> List.append import_list

in

{ list = ImportMap.to_json importmap; modules = ImportMap.to_module importmap }

;;

HTML Helpers

We now need functions to map the Assets and generate the HTML tags for both the Import Map and the preloaded modules:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

let path ?(path = "static/") filename =

match StringMap.find_opt (path ^ filename) A.asset_map with

| Some fingerprinted_filename -> "/" ^ fingerprinted_filename

| None -> "/" ^ path ^ filename

;;

module PureHTML = struct

open Pure_html

open HTML

let importmap_tag =

let importmap_list = script [ type_ "importmap" ] "%s" A.importmaps.list in

let preloaded_modules =

List.map

(fun file -> link [ rel "modulepreload"; href "%s" file ])

A.importmaps.modules

in

null @@ (importmap_list :: preloaded_modules)

;;

end

module String = struct

let importmap_tag =

let importmap_list =

Format.sprintf {|<script type="importmap">%s<script>|} A.importmaps.list

in

let preloaded_modules =

List.map

(fun file -> Format.sprintf {|<link rel="modulepreload" href="%s">|} file)

A.importmaps.modules

in

List.to_string ~sep:"\n" (fun s -> s) (importmap_list :: preloaded_modules)

;;

end

Introducing RealityAssets

Clearly, this is a lot of reusable code for any Dream-based web project. So, I’ve bundled it into RealityAssets — a library that:

- Handles asset fingerprinting automatically.

- Generates Import Maps for local and external JS dependencies.

- Adds Stimulus boilerplate.

- Includes a CLI for setup and integration.

Putting It to the Test

Now that RealityAssets is set up, let’s use it.

- Update the CSS import to use the fingerprinted path.

- Initialize the Import Map with Stimulus.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

open Pure_html

open HTML

module Assets = Client.Assets

let body_classes =

"grid h-screen overflow-hidden grid-cols-[auto_minmax(0,1fr)] \

grid-rows-[minmax(0,1fr)_auto] bg-gray-900 text-white"

;;

let layout ?(page_title = "QuestComplete") data =

html

[ lang "fr" ]

[ head

[]

[ meta [ charset "UTF-8" ]

; meta [ name "viewport"; content "width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" ]

; title [] "%s" page_title

; link [ rel "stylesheet"; href "%s" (Assets.path "application.css") ]

; Assets.PureHTML.importmap_tag

; Assets.PureHTML.js_entrypoint_tag

]

; body

[ class_ "%s" body_classes ]

[ header [ class_ "min-h-0 min-w-0" ] []

; main [ class_ "min-h-0 min-w-0 overflow-y-auto" ] data

; footer [ class_ "min-h-0 min-w-0" ] []

]

]

;;

Vanilla JS

Next, let’s try some Vanilla JavaScript:

1

2

3

// Previous content that loads Stimulus Controllers

console.log("Hello from application.js")

Stimulus JS

And now, some Stimulus JS:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

import { Controller } from "@hotwired/stimulus"

export default class extends Controller {

connect() {

console.log('Hello, Stimulus!', this.element)

}

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

let render game =

let data = extract_data_from game in

Layouts.Main.layout

[ h1

[ class_ "text-red-800 text-4xl"; string_attr "data-controller" "hello-world" ]

[ txt "%s" data.title ]

; img [ src "%s" data.cover_url; alt "%s" data.title; class_ "w-1/4" ]

; ul

[]

[ li [] [ txt "Genre : %s" data.genre ]

; li [] [ txt "Date de sortie : %s" data.release_date ]

; li [] [ txt "Plateforme : %s" data.platform ]

]

; br []

; br []

; p [ class_ "text-bold" ] [ txt "Complété le %s" data.completion_date; txt " !" ]

; a [ href "/games" ] [ txt "Back" ]

]

|> to_string

;;

Final Thoughts

With this setup, we now have:

✅ Automatic asset fingerprinting ✅ Import Maps handling both local and external JS ✅ Seamless Stimulus integration ✅ PureHTML support for easier templating

One small issue remains: string_attr isn’t the safest way to add Stimulus attributes. I’ll propose a pull request to add Stimulus tags to Dream_html, similar to its existing HTMX module. If it’s not accepted, I’ll create a separate module for myself.

And that’s it! 🚀

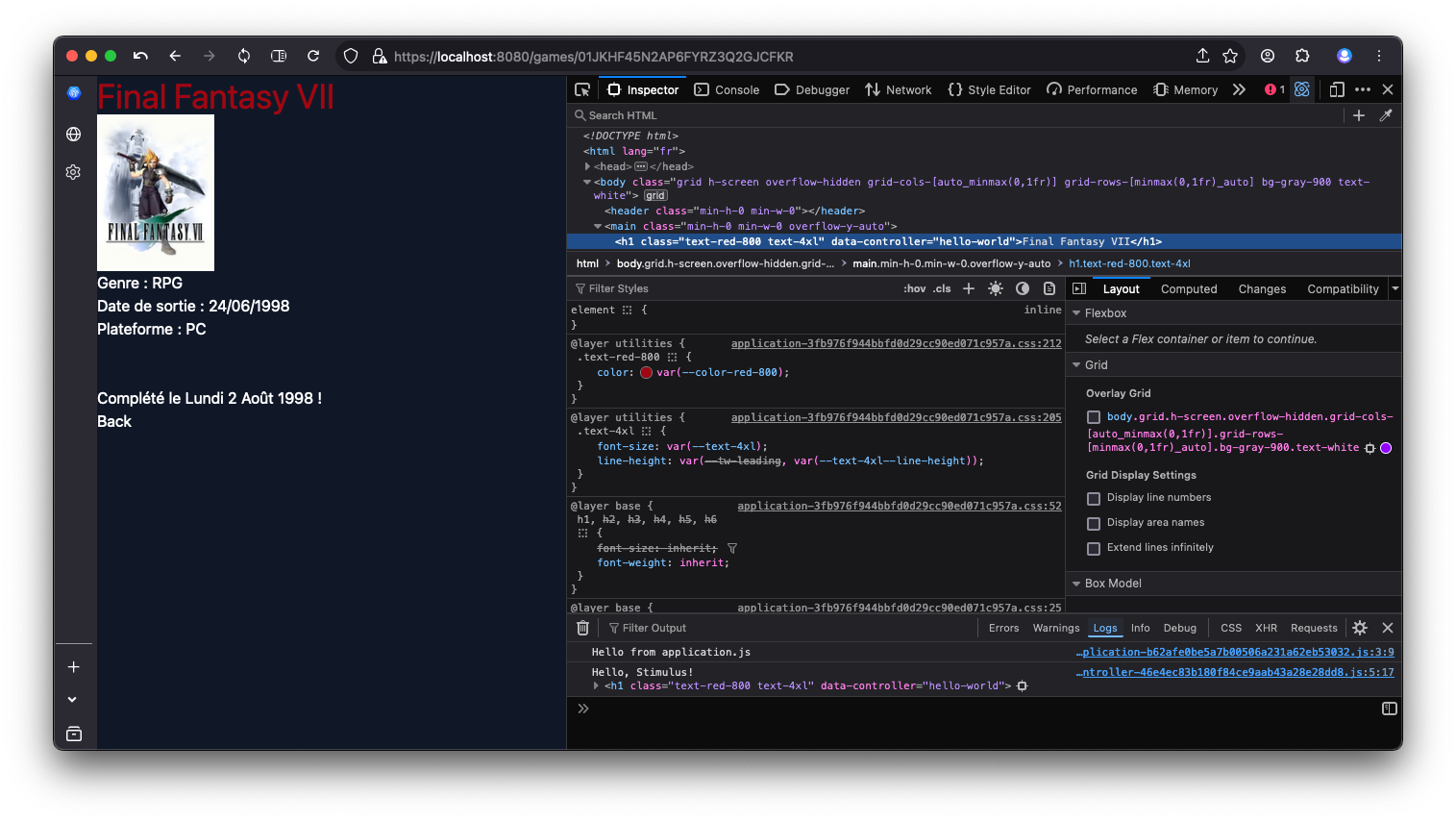

One of our pages with Vanilla and Stimulus JS ‘Hello World’

One of our pages with Vanilla and Stimulus JS ‘Hello World’

Next Steps

As always, I have plenty of ideas, and I rarely end up following my own roadmap—but that’s half the fun, right? That said, there are still a few critical pieces to tackle before I can call this a functional proto-framework:

- WebSockets – Real-time functionality is essential for many modern web applications, and I’ll need to explore the best way to integrate it into my setup.

- Authentication – WebAuthn is already in the work, but there are still improvements to be made for a seamless authentication flow.

- Database Migrations – Managing schema changes effectively is a must-have for any serious web project.

Once these are in place, I’ll have a strong foundation to build on. Whether this eventually turns into a full-fledged framework or just a personal toolkit remains to be seen, but one thing is certain—I’m enjoying the process!

Stay tuned for the next post, and as always, feel free to reach out if you have any thoughts, questions, or suggestions.